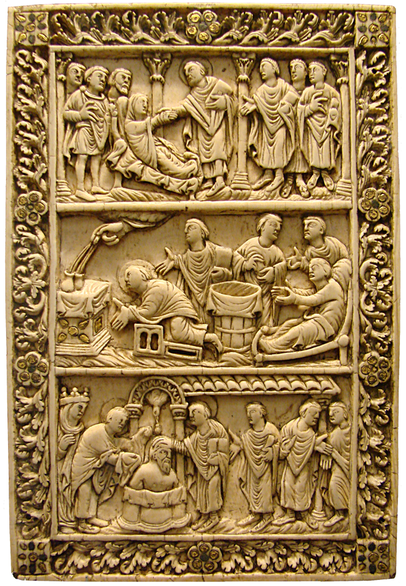

Ivory book cover, Reims, 9th century, Museum of Picardy in Amiens,

scenes from St. Remi’s life, the lower segment the baptism of Clovis.

Ivory book cover, Reims, 9th century, Museum of Picardy in Amiens,

scenes from St. Remi’s life, the lower segment the baptism of Clovis.

St. Clothilde c 475 - 545

Ancestral Roots 240A:3

Clothilde, daughter of King Chilperic of Burgundy, 2nd wife to Clovis I, King of the Franks, mother to daughter Clothilde and 3 future Merovingian kings, Chlodomer, Childebert I, and Chlothar I. Clothilde was born at the Burgundian court of Lyon in 475, educated in the Catholic Christian faith at a time when the Western Roman Empire had became fragmented under the impact of various ‘barbarian’ invasions and theology tended to be more localized and diverse. Burgundians were largely a catholic people while other tribes in the area had adopted the beliefs of Arianism, a major theological movement at the time speculating into the nature of Christ, and the Franks remained pagan.

Clothilde’s father Chilperic II ruled Burgundy with his father Gondioc until Gondioc’s death in 473 when Burgundy was partitioned with his younger brothers Godegisel, Gundobad, and Godomar. In 493, after Chilperic’s brother Gundobad who had already murdered their brother Godomar in 486, turned on Chilperic, assassinating Chilperic, downing his wife, and exiling Chilperic’s two daughters, Chroma who became a nun and Clothilde who fled to her uncle Godegisel.

Ancestral Roots 240A:3

Clothilde, daughter of King Chilperic of Burgundy, 2nd wife to Clovis I, King of the Franks, mother to daughter Clothilde and 3 future Merovingian kings, Chlodomer, Childebert I, and Chlothar I. Clothilde was born at the Burgundian court of Lyon in 475, educated in the Catholic Christian faith at a time when the Western Roman Empire had became fragmented under the impact of various ‘barbarian’ invasions and theology tended to be more localized and diverse. Burgundians were largely a catholic people while other tribes in the area had adopted the beliefs of Arianism, a major theological movement at the time speculating into the nature of Christ, and the Franks remained pagan.

Clothilde’s father Chilperic II ruled Burgundy with his father Gondioc until Gondioc’s death in 473 when Burgundy was partitioned with his younger brothers Godegisel, Gundobad, and Godomar. In 493, after Chilperic’s brother Gundobad who had already murdered their brother Godomar in 486, turned on Chilperic, assassinating Chilperic, downing his wife, and exiling Chilperic’s two daughters, Chroma who became a nun and Clothilde who fled to her uncle Godegisel.

|

During this same period there were significant marriages uniting the dynasties of barbaric Europe, generally serving to strengthen the position of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths (475–526), ruler of Italy (493–526), regent of the Visigoths (511–526), and a patrician of the Roman Empire. Clovis became drawn into the web of matrimonial alliances when Theodoric married his sister Audofleda. In 493 Clovis asked for Clothilde’s hand in marriage after learning of the recent Burgundian events and Clothilde’s situation; Gundoad was unable to decline. There are various theories as to Clovis’s motivation for the marriage, whether as Gregory of Tours, the historiographer, suggests it was a calculation to create uneasiness with Gundoad or more simply a way to connect to the powerful Theodoric will never be known, but in 493, at 23 years of age, Clothilde became Clovis’ wife.

|

During this same period there were significant marriages uniting the dynasties of barbaric Europe, generally serving to strengthen the position of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths (475–526), ruler of Italy (493–526), regent of the Visigoths (511–526), and a patrician of the Roman Empire. Clovis became drawn into the web of matrimonial alliances when Theodoric married his sister Audofleda. In 493 Clovis asked for Clothilde’s hand in marriage after learning of the recent Burgundian events and Clothilde’s situation; Gundoad was unable to decline. There are various theories as to Clovis’s motivation for the marriage, whether as Gregory of Tours, the historiographer, suggests it was a calculation to create uneasiness with Gundoad or more simply a way to connect to the powerful Theodoric will never be known, but in 493, at 23 years of age, Clothilde became Clovis’ wife.

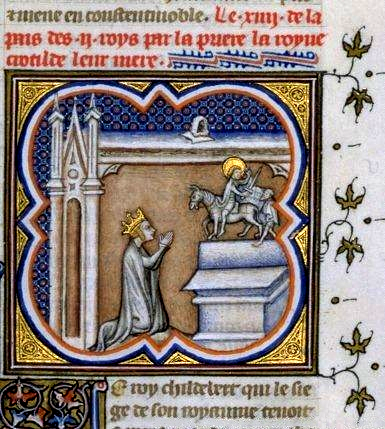

Again, according to Gregory of Tours, Clovis remained pagan refusing to be persuaded to convert to Christianity even with Clothilde’s “preaching to her husband unceasingly” until 496 when Clovis and his army were facing utter destruction in the Battle of Tolbiac. Concerned with the outcome of the battle Clovis took an oath to convert to Catholic Christianity if they were victorious. Clovis won the battle and became the first of the German kings to embrace the Catholic brand of Christianity to which the native Roman population belonged.

Regardless of the specific date, whether in 496 or, as suggested from a letter written by Clovis in 507, the first official document to survive from a Merovingian king, wherein Clovis explains to his bishops that en route to ‘Vouille’, the Frankish campaign of invasion of Visigothic Aquitaine, he had issued an edict protecting Church property. Nonetheless, at some point, Clovis did convert to Catholic Christianity and was baptized probably in 508; other Franks followed their master to the font, but not the 3,000 reported by Gregory who may have been more concerned creating the image of a Catholic king over strictly reporting the facts.

Clovis died in 511 and is considered “the first king of what would become France.” Clotilde occupied herself with the building of churches and monasteries, founding a convent for young girls of nobility before it was destroyed by the Normans in 911, replaced in the 13th century with Our Lady’s Collegiate Church Les Andelys, Normandy. Clotilde retired to a monastery where she spent the remaining 34 years of her life, dying at age 75 and was buried at her husband's side in the Church of the Holy Apostles (now the Abbey of St Genevieve), leaving a legacy as the woman who brought Christianity to France.

Again, according to Gregory of Tours, Clovis remained pagan refusing to be persuaded to convert to Christianity even with Clothilde’s “preaching to her husband unceasingly” until 496 when Clovis and his army were facing utter destruction in the Battle of Tolbiac. Concerned with the outcome of the battle Clovis took an oath to convert to Catholic Christianity if they were victorious. Clovis won the battle and became the first of the German kings to embrace the Catholic brand of Christianity to which the native Roman population belonged.

Regardless of the specific date, whether in 496 or, as suggested from a letter written by Clovis in 507, the first official document to survive from a Merovingian king, wherein Clovis explains to his bishops that en route to ‘Vouille’, the Frankish campaign of invasion of Visigothic Aquitaine, he had issued an edict protecting Church property. Nonetheless, at some point, Clovis did convert to Catholic Christianity and was baptized probably in 508; other Franks followed their master to the font, but not the 3,000 reported by Gregory who may have been more concerned creating the image of a Catholic king over strictly reporting the facts.

Clovis died in 511 and is considered “the first king of what would become France.” Clotilde occupied herself with the building of churches and monasteries, founding a convent for young girls of nobility before it was destroyed by the Normans in 911, replaced in the 13th century with Our Lady’s Collegiate Church Les Andelys, Normandy. Clotilde retired to a monastery where she spent the remaining 34 years of her life, dying at age 75 and was buried at her husband's side in the Church of the Holy Apostles (now the Abbey of St Genevieve), leaving a legacy as the woman who brought Christianity to France.

Reference and Further Reading

- Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/gregory-clovisconv.asp.

- Geary, Patrick J.. Readings in Medieval History, Peterborough, Ont. 1991.

- Robinson, James Harvey, editor. Readings in European History: Vol. I. Boston, 1905.

- Schaus Margaret, editor. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe, An Encyclopedia. Routledge Taylor & Francis Groups, 2015.

- Tierney, Brian. The Middle Ages, Volume I: Sources of Medieval History, 5th ed. New York, 1992.

- Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms 450-751. Pearson Education, 1994.