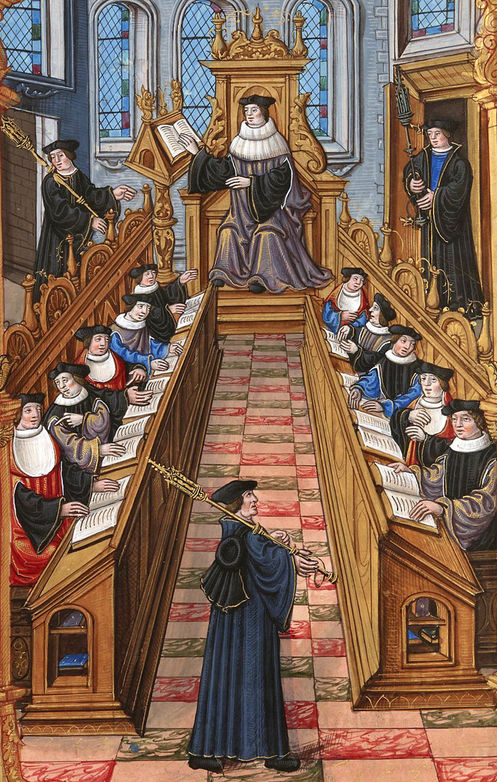

Chants royaux, Meeting of doctors at University of Paris, 1537 CE

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, folio 27v.

Chants royaux, Meeting of doctors at University of Paris, 1537 CE

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, folio 27v.

Jacqueline Felice de Almania, c 1322, reportedly from Florence. Early 14th century Paris’ population was more than 200,000 and about 38 medical practitioners yet 1292 records indicate only eight female physicians were registered.

Healing was generally regarded as the natural responsibility of mothers and wives with techniques learned from family, friends or from observation of other healers. Excluded from academic institutions female healers of the Middle Ages had little opportunity to contribute to the science of medicine, rather serving as herbalists, midwives, barber-surgeons, and nurses.

The University of Paris and its medical faculty in the 13th century were less tolerant of female healers promoting royal, religious and academic decrees to restrict the practice of medicine to licensed physicians only. Since women were ineligible for university training and the minor clerical vows that were required of all candidates for licensure the inevitable result was to ensure that legal healing became a male monopoly.

In 1322, Jacqueline was put on trial for unlawful practice yet male physicians were rarely, if ever, brought to court for similar charges. During the trial the medical faculty reminded the court that for sixty years penalties of fines and excommunication had been in operation against the ignorant and illicit practicing in Paris and had been applied with the full force. The faculty claimed that Jacqueline had persisted in acting as a physician by visiting the sick, examining their urine and pulse, touching and palpating their bodies, contracting with the patient for her payment if she cured them and prescribing and administering various drugs yet was totally ignorant of the art of medicine and was not lettered. The testimony of eight witness, seven former patients plus the wife of one of them, is recorded in the trial record all affirm her medical procedures but deny that she ever demanded money from them in advance of the cure. During several testimonies there was discussion that she had successful cured her patients after other physicians had failed and given up hope of the patient's recovery. The court reasoned that it was obvious that a man could understand the subject of medicine better than a woman because of his gender. The prosecution’s entire case was based upon the absence of formal training credentials yet not a single effort was made to test her knowledge and understanding of disease and it’s management. She was banned from practicing medicine and threatened with excommunication if she ever did so again. This decision is considered to have banned women from academic study in medicine in France and obtaining licenses until the 19th-century.

Healing was generally regarded as the natural responsibility of mothers and wives with techniques learned from family, friends or from observation of other healers. Excluded from academic institutions female healers of the Middle Ages had little opportunity to contribute to the science of medicine, rather serving as herbalists, midwives, barber-surgeons, and nurses.

The University of Paris and its medical faculty in the 13th century were less tolerant of female healers promoting royal, religious and academic decrees to restrict the practice of medicine to licensed physicians only. Since women were ineligible for university training and the minor clerical vows that were required of all candidates for licensure the inevitable result was to ensure that legal healing became a male monopoly.

In 1322, Jacqueline was put on trial for unlawful practice yet male physicians were rarely, if ever, brought to court for similar charges. During the trial the medical faculty reminded the court that for sixty years penalties of fines and excommunication had been in operation against the ignorant and illicit practicing in Paris and had been applied with the full force. The faculty claimed that Jacqueline had persisted in acting as a physician by visiting the sick, examining their urine and pulse, touching and palpating their bodies, contracting with the patient for her payment if she cured them and prescribing and administering various drugs yet was totally ignorant of the art of medicine and was not lettered. The testimony of eight witness, seven former patients plus the wife of one of them, is recorded in the trial record all affirm her medical procedures but deny that she ever demanded money from them in advance of the cure. During several testimonies there was discussion that she had successful cured her patients after other physicians had failed and given up hope of the patient's recovery. The court reasoned that it was obvious that a man could understand the subject of medicine better than a woman because of his gender. The prosecution’s entire case was based upon the absence of formal training credentials yet not a single effort was made to test her knowledge and understanding of disease and it’s management. She was banned from practicing medicine and threatened with excommunication if she ever did so again. This decision is considered to have banned women from academic study in medicine in France and obtaining licenses until the 19th-century.

References and Further Reading

- Ballester, Luis Garcia, Roger French, Jon Arrizabalaga and Andrew Cunningham, editors. Practical medicine from Salerno to the Back Death. Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, Cambridge University. 1994.

- Howard, Sethanne. The Hidden Giants. Washington Academy of Science, 2012.

- Green, Monica H. Getting to the Source: The Case of Jacoba Felicie and the Impact of the Portable Medieval Reader on the Canon of Medieval Women’s History. //ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1057&context=mff

- “Women Healers of the Middle Ages: Selected Aspects of Their History.” Minkowski, William L. American Journal of Public Health. Feb 1992, Vol. 82. No. 2, p 293. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1694293/pdf/amjph00539-0138.pdf.